A Watcher in the Woods, by Florence Engel Randall

Note: The original 1976 book was titled A Watcher in the Woods. Four years later, it was republished as The Watcher in the Woods to coincide with the Disney movie. These are the things that make life confusing.

Fifteen-year-old Jan isn't particularly excited about moving from Ohio to a small town in Massachusetts:

I didn't belong in any forest. I didn't belong in a lonely house set at the edge of woods or in a small town like Bywater where everyone knew everyone else and strangers remained strangers. (8)

Once her family chooses a house—one in the middle of nowhere with a Tragically Mysterious Past, one that Jan just KNOWS is dangerous in some way—Jan is even less enthused:

They like the house, I told myself incredulously. They are going to love every bit of it, and what am I going to do? They don't know that something is watching and waiting there in the woods. (16)

Before Mrs. Aylwood, the house's previous owner, moves out she tells Jan a little bit about the Mysterious Tragedy attached to the house. Almost fifty years ago, Mrs. Aylwood's daughter, Karen, went for a walk in the woods... and she never returned. Search parties did what they could, but no one ever found a trace of her. The townspeople assumed that Karen ran away, but Mrs. Aylwood is convinced that somehow, she's still out there.

Anddd then, after dropping that bomb, she moves out and Jan's family moves in. Creepiness ensues—multiple mirrors crack, seven-year-old Ellie starts writing strange backwards messages, and Jan continues to feel some sort of PRESENCE in the woods.

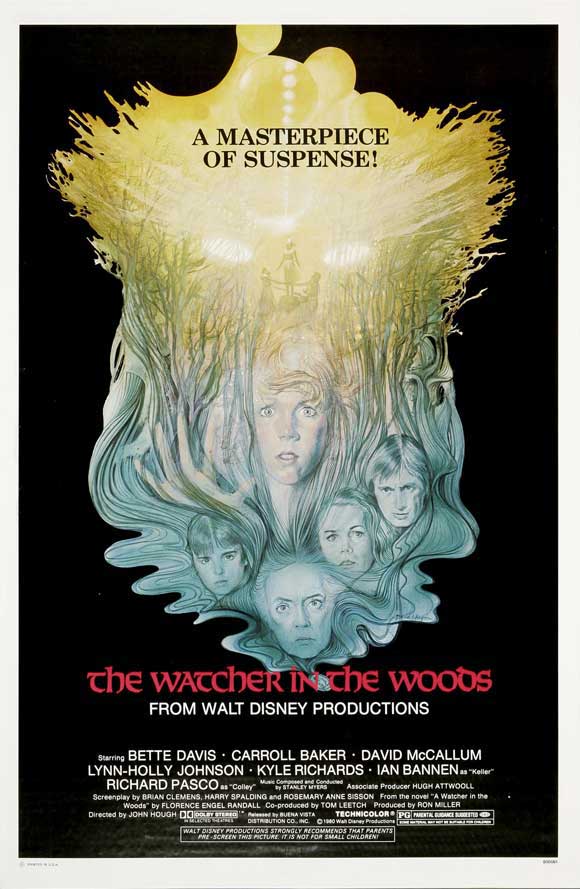

I remember being terrified by this movie as a kid, but beyond it starring Bette Davis, I can't remember a thing about it. I have no idea if the plot was even as remotely incomprehensibly bonkers as this book is—based on the trailer, it looks like in additon to ramping up the action, the screenwriters dispensed with the telepathic people from a futuristic alternate dimension?

Because, yes. That's where Karen went. She accidentally walked through an interdimensional portal—an interdimensional portal that appears once every fifty years in a rectangle-shaped opening in a tree, because WHY NOT?—and got stuck on the other side:

It was a giant oak, its trunk so thick, so huge that even if the three of us had held hands with our arms outstretched, we couldn't have encircled it. The opening was in the shape of an enormous rectangle, each corner angled so smoothly, mitered so precisely, that it seemed almost man-made. (82)

Much of the prose and dialogue is somewhat stilted, and Randall was clearly a huge fan of adverbs—the whole thing feels VERY 70s. This following passage is a good example of the writing style:

"And ceilings that are high enough for a human being," my father said ruefully. He rubbed his forehead, and I knew he was remembering how many times in the last few hours he had bumped it, my tall father exaggeratedly stooping in dormered bedrooms and hunching through doorways. (2)

I checked and re-checked that paragraph, and I didn't miss a sentence or transcribe it incorrectly or anything. That's just how it's written. There's also a LOT of stuff along the lines of this:

Ever after, I repeated silently. Ever after what? The events that came before, of course, but how long did the after last? How could you measure ever after, and what did the once upon a time mean? Didn't you have to be in a time?

Right now we were living in a time. We were not soaring to a dizzy perch upon a time. This was one second of one minute of one hour of one day of one month of one year of one decade of one century. We were driving down the road, the three of us sitting still in one moving vehicle. We are traveling in time, and for a certain time, and at one and the same time, we were also moving in space. (56)

Which makes for tough reading, as it makes much of the book read like a sub-par knockoff of A Wrinkle in Time. Also, the brief engagement with the issues surrounding elder care feels less about the issues and more about finessing the plotting:

"...Do you know what Mrs. Aylwood told me? She said there's an infirmary, but if anyone gets really sick, they're not allowed to stay. They have to go to a hospital, and if the hospital won't keep them, then the only thing that's left is a nursing home. Why should the old be shoved aside?" Mark asked savagely. (162)

But there are some great bits, too! Some strong descriptions and images:

She had stopped frowning, but the lines between her eyes remained, the impression of them traced there lightly. (51)

But the strengths are mostly in regards to Randall's portrayal of Jan as an out-of-sorts teenager. I loved this next part, which is a perfect monologue of a fifteen-year-old who is SUPREMELY CRANKY about being stuck in the car all day with her entire family, about being dragged by a real estate agent to look at house after house after house:

I closed my eyes. Who wanted to see them? No one with any sense had ever daydreamed about a cow. I didn't want to look at the back of Mrs. Thayer's head and the back of my father's head any longer. I didn't want to turn to the right and study my mother's profile. I didn't want to turn to the left and watch Ellie's ponytail bob up and down. (7)

And I loved this next line. What she's saying isn't inaccurate—this is the burden of the Older Sister—but her tone is so wonderfully put-upon and world-weary that it made me laugh out loud:

At the age of seven there were a lot of things Ellie didn't want to do, and didn't. At fifteen there were a lot of things I had to do, and did. (3)

As a tween, though, reading that line would have made me felt SO understood. But I will say that even as an ADULT, I was offended on Jan's behalf by this one:

"Because," my mother always said, laughing, "there has to be some benefit in having children spaced so far apart. Like having a built-in babysitter." (23)

So overall, despite a whole lot of weird phrasing and a storyline that felt like it was based on three random words plucked out of a hat, Randall really has some thoughtful things to say about the in-betweenness of being a young teenager. For instance, this bit from Mrs. Aylwood:

As if I had spoken out loud, she said, "I can remember it so well. Isn't that odd? Fourteen isn't too difficult, and sixteen is much easier because you feel as if you are on your way; but when you are fifteen, you are an in-between. Neither a child any longer nor beginning to be grown-up. It was different in my time. Even though the days seemed to last longer, we all seemed to age a lot faster. When a girl was sixteen, she considered herself a woman and was dreaming lovely, romantic dreams about falling in love and having children of her own. But everything was different then. That doesn't mean it was better, mind you. It was just different." (30-31)

AND. Jan's parents not only pick up on—and buy into—the woo-woo, they actively get involved in working to solve the mystery. Not without qualms—and yes, they're worried and protective about their children and so on—and OF COURSE it's the mother who's more protective, but that actually works pretty well because of the Mrs. Aylwood backstory:

"Mrs. Aylwood can't do it alone," I said painfully. "She needs Ellie and me. We all need to hold hands."

"Paul," my mother said. She turned around and now her eyes were wet. "Are you going to tell me that we have to risk our own children?"

"'Hostages to fortune,'" my father quoted soberly. "Just having children is a risk, Kate. We are gambling on the future, investing in the unknown with nothing but hope and blind faith. How can we keep our own safe when anyone else is in danger?" (152)

Rather than acting as obstacles or detracting from Jan's agency and freedom, they ultimately help to bring about the happy(ish) ending. I'm certainly not looking for adult characters to take over youth fiction, but it is nice to see them be, you know, at least occasionally SEMI-competent and reasonable.